The CSRD Challenge: What Do Carbon Audits Require?

Inside the technical demands of a CSRD emissions engagement.

The First Reports Are In, and the Problems Are Already Visible

PwC’s review of the first 100 CSRD-compliant sustainability statements, published in 2025 covering fiscal year 2024, laid bare the CSRD challenge facing the profession. The findings showed wide variation in quality. Some reports ran to over 300 pages, others barely reached 30. Some companies disclosed more than 80 impacts, risks and opportunities. Others identified fewer than 15. A small number received qualified conclusions from assurance practitioners. Many more contained Emphasis of Matter and Inherent Limitation paragraphs, with auditors flagging high levels of measurement uncertainty on quantitative metrics, problems comparing sustainability data between entities and over time, and weaknesses in the double materiality assessment process.

For ESG practitioners at accounting firms now preparing to take on CSRD assurance and advisory engagements, these findings are not abstract. They are a preview of what will be sitting on your desk. The question is whether you know how to deal with it.

Step One: Accepting the Engagement and Assembling the Right Team

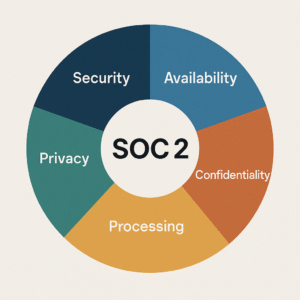

Under ISAE 3410 (Assurance Engagements on Greenhouse Gas Statements) and the newer ISSA 5000 standard, the engagement partner must confirm that the team has both assurance competencies and GHG-specific technical knowledge before accepting. This is not a formality. Carbon accounting involves scientific and engineering concepts that traditional audit training does not cover: global warming potentials, CO2 equivalents, the distinction between biogenic and fossil carbon, the difference between location-based and market-based Scope 2 accounting, and the application of emission factors drawn from databases like the UK’s DEFRA conversion factors, the US EPA’s supply chain factors, or the IEA’s grid emission factors.

If your team does not include someone who understands why a kilowatt-hour of electricity in Poland has a different carbon intensity than one in France, or why using a 2018 EPA spend-based emission factor in a 2025 engagement introduces inflation distortion, you are not ready. ISAE 3410 explicitly contemplates that more complex engagements may require scientific and engineering expertise alongside assurance skills. Many firms are hiring environmental scientists and sustainability specialists into their ESG assurance teams for exactly this reason.

Step Two: Testing the Organisational Boundary

Before you can assess whether a client’s emissions figures are right, you need to establish whether they are measuring the right things. The GHG Protocol offers two approaches to defining the organisational boundary: the equity share approach and the control approach (which splits into financial control and operational control). The choice matters. A manufacturing group that consolidates a 40% joint venture under operational control will report different Scope 1 figures than one using equity share.

In the first wave of CSRD reports, PwC observed that many companies said little about how they defined their consolidation boundary for sustainability reporting or how it related to their financial reporting boundary. This represents a core dimension of the CSRD challenge for assurance practitioners: if the boundary is wrong, every number built on top of it is unreliable. Your first procedure should be obtaining the client’s documented boundary definition, tracing it back to the GHG Protocol methodology they claim to follow, and testing whether the entities, sites and operations included are consistent with that methodology. If the client reports on 90% of revenue-generating entities but excludes a subsidiary with significant manufacturing emissions, you need to evaluate whether that omission is material.

Step Three: Walking Through the Emissions Calculation

The actual carbon calculation is deceptively simple in theory: activity data multiplied by an emission factor equals emissions in tonnes of CO2 equivalent. In practice, this is where the CSRD challenge becomes most tangible, where most errors occur, and where the practitioner’s technical judgment is tested.

For Scope 1, you are looking at fuel combustion records, refrigerant logs and process emissions data. The common mistakes here involve unit conversions (litres to kilogrammes, gross versus net calorific values), incorrect emission factors for fuel type, and missing fugitive emissions from refrigerant leaks. A client may have recorded their natural gas consumption in cubic metres but applied an emission factor denominated in kilowatt-hours without converting. This is a mechanical error, but it can move the final figure by 10% or more. Your job is to obtain the source data (invoices, meter readings, fuel purchase records), recalculate a sample of emissions lines independently, and check that the emission factors used match the fuel type, geography and reporting year.

For Scope 2, the key question is whether the client is reporting on a location-based method, a market-based method, or both (the GHG Protocol requires both to be disclosed). If a client holds Renewable Energy Certificates or has a Power Purchase Agreement and claims zero market-based Scope 2 emissions, you need to inspect the certificates, verify the contractual arrangements, and confirm that the instruments meet the GHG Protocol’s quality criteria for market-based accounting. Misapplication of RECs is one of the most common sources of misstatement in Scope 2 reporting.

Step Four: Tackling the Scope 3 Minefield

Scope 3 is where engagements get genuinely difficult, and where the CSRD challenge is at its most acute. It covers 15 categories of indirect emissions across the value chain, and for most companies it represents the largest share of their total footprint. Under CSRD, Scope 3 reporting is mandatory where these emissions are material, which for most sectors they will be.

The practitioner needs to understand exactly what calculation method the client has used for each material category and why. The three main approaches are the supplier-specific method (using primary data from suppliers), the activity-based method (using physical quantities like tonnes of material or kilometres of freight), and the spend-based method (using procurement expenditure multiplied by environmentally extended input-output emission factors).

Most clients will present a hybrid. They may have supplier-specific data for their top 10 raw material suppliers but use spend-based estimates for everything else. Your procedures here include testing whether the client’s screening of Scope 3 categories is complete (did they consider all 15 and document why any were excluded?), evaluating whether the calculation method chosen for each category is appropriate given available data, checking the emission factor sources and vintage, and assessing the reasonableness of any extrapolations or proxies.

A specific trap to watch for: spend-based emission factors are derived from economic input-output models that reflect industry averages, not supplier-specific performance. They are also sensitive to price changes. If a client’s procurement costs rose 15% due to inflation, the spend-based method will show a 15% increase in emissions even if the physical activity did not change. If the client reports a Scope 3 reduction alongside rising procurement costs, probe the methodology carefully. The GHG Protocol’s Technical Guidance for Calculating Scope 3 Emissions recommends prioritising more specific methods for significant emission sources and reserving spend-based estimates for less material categories.

Step Five: Evaluating the Double Materiality Assessment

The double materiality assessment determines which ESRS topics appear in the sustainability statement, so it sits upstream of everything else. In PwC’s first-100-reports analysis, there was high variability in how companies conducted and disclosed their DMA. Many said they engaged internal stakeholders but were vague about external engagement. Some explained why certain topics were omitted. Many did not.

As the assurance practitioner, you are required to evaluate whether the DMA process complies with ESRS 1 requirements. In practical terms, this means reviewing the client’s list of identified IROs, the scoring criteria applied (severity, likelihood and magnitude for impact materiality; likelihood and magnitude of financial effects for financial materiality), the thresholds used for determining what is material, and whether the documentation supports the conclusions reached. A common pitfall highlighted by EFRAG’s feedback is that companies assess the likelihood and magnitude of a risk itself rather than the likelihood and magnitude of the financial effects of that risk, which is what ESRS 1 actually requires. This subtle but critical distinction encapsulates the CSRD challenge for practitioners: the standards demand precision that many clients have not yet internalised. If your client has scored “climate transition risk” as high severity but cannot articulate the estimated financial impact on cash flows or cost of capital, the DMA may not meet the standard.

Step Six: Forming Your Conclusion

Under limited assurance, you conclude in the negative: “nothing has come to our attention” to indicate material misstatement. This is a lower bar than reasonable assurance, but it is not a rubber stamp. You need sufficient evidence to support that conclusion, and you need to document your procedures, findings and professional judgments in a way that would withstand regulatory inspection.

EFRAG’s cost-benefit analysis estimates that limited assurance will cost at least €360,000 per year for large listed companies after all requirements are phased in, with first-year costs running roughly 30% higher due to the effort of establishing new systems and procedures. Reasonable assurance, if it comes, would more than double that figure. If a client cannot provide you with the evidence trail you need (source data for activity figures, documented emission factor selections, a robust DMA with clear rationale for materiality conclusions), you may be looking at a scope limitation. The CSRD challenge for the assurance provider is knowing when to push back. And where value chain information is missing despite reasonable efforts by the client, Accountancy Europe’s guidance makes clear that a qualified conclusion or emphasis of matter paragraph may be necessary.

What This Means for Your Day-to-Day Work

The CSRD assurance engagement is not a desk review of a glossy sustainability report. It is a technical engagement that requires you to trace emissions figures back to invoices and meter readings, challenge emission factor selections, test organisational boundaries against GHG Protocol methodology, and evaluate the professional judgments embedded in a double materiality assessment. Around 74% of companies are still managing their sustainability data in spreadsheets, according to PwC’s 2024 Global CSRD Survey, and a separate PwC Luxembourg study found 55% expect challenges with data quality and consistency. The evidence you need will often not be waiting for you in a neat package.

The firms already succeeding at this work are the ones that have invested in training their assurance teams on GHG Protocol methodology, hired technical specialists who understand emission factor databases and calculation approaches, and built engagement workflows that mirror the structure of a carbon audit rather than treating it as a bolt-on to the financial audit. The Omnibus I simplification, which prompted EFRAG to reduce mandatory ESRS data points by 61% and narrowed CSRD scope to companies with more than 1,000 employees and €450 million in turnover, has not changed the technical demands of the work. It has simply concentrated the CSRD challenge on larger, more complex engagements where the stakes and the scrutiny are higher.

If you are an ESG accountant preparing for your first CSRD assurance engagement, start with the evidence. Everything else follows from there.