Digital Solutions for Document Management in Restructuring and Insolvency Cases

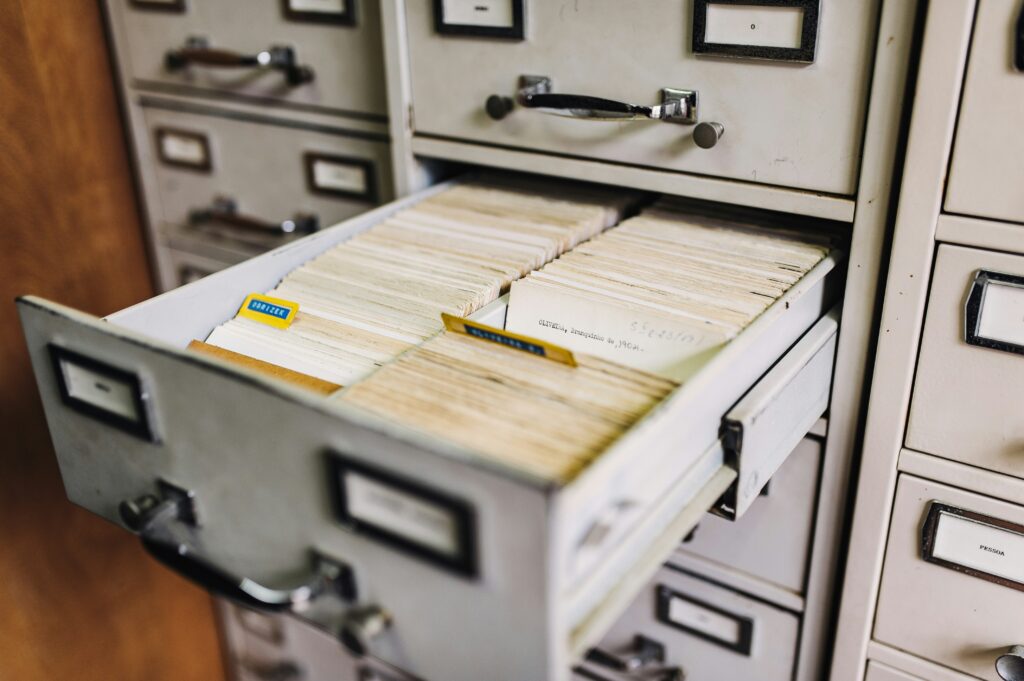

The insolvency profession has spent the better part of a decade discussing digital transformation while doing remarkably little about it. Walk into most restructuring practices and you will still find filing cabinets, physical creditor files, and processes that would be familiar to practitioners from the 1990s. The irony of professionals who advise failing businesses on modernization while clinging to paper-based systems themselves has not gone unnoticed. Yet something has shifted in the past two years. Document management, once the preserve of larger advisory firms with technology budgets to burn, is becoming standard infrastructure. The catalyst was not visionary leadership but sheer necessity: remote work during the pandemic made paper files untenable. What began as improvisation is hardening into permanent change, with consequences that extend well beyond where documents live.

The Economics of Delay

Consider what document mismanagement actually costs in insolvency work. When administrators at the UK Insolvency Service implemented new digital systems with IBM Consulting, processing times for claims fell by 75%. That is not a marginal improvement. It represents the difference between distributing funds to creditors in weeks rather than months, between closing a case efficiently and watching it drag on while administrative costs mount.

The time sink is not usually catastrophic failures (lost files or major errors) but accumulated friction. A creditor queries a claim; the administrator must locate the original submission, any supporting documentation, and prior correspondence before responding. With paper files, this might take an hour. With digital systems and proper search functionality, it takes minutes. Multiply that across hundreds of creditor interactions in a complex case and the time savings become substantial.

More insidious is the cost of poor version control. Restructuring proposals evolve through multiple drafts as terms are negotiated. Paper-based systems rely on practitioners carefully tracking which version is current. Digital platforms make this automatic. The risk is not that someone accidentally works from an old version (though that happens) but the wasted time verifying which draft is correct before making decisions.

What Money Actually Buys

The technology itself is unremarkable. Centralized cloud storage, automated workflows, granular access permissions: these are solved problems in enterprise software. What distinguishes insolvency-specific platforms like Virtual Cabinet is understanding the particular choreography of restructuring work: creditor hierarchies, regulatory filing requirements, the need to wall off confidential information from certain stakeholders while sharing it with others.

The real value lies in automation of tedious compliance work. Insolvency practitioners operate under heavy regulatory oversight. Every document must be retained, every access logged, every piece of sensitive data protected according to strict protocols. Manual compliance is labor-intensive and error-prone. Digital systems handle it as a byproduct of normal operations, generating comprehensive audit trails without anyone thinking about them.

This matters more as regulatory requirements tighten. European data protection rules impose substantial obligations around handling personal and financial information. Meeting these requirements manually requires dedicated compliance effort. Automated systems build compliance into the workflow, reducing both cost and risk.

Cross-Border Imperatives

International restructurings expose the limitations of traditional document management most brutally. A case spanning multiple jurisdictions might involve administrators in London, creditors’ committees in New York and Frankfurt, local counsel across several countries, and various advisers and stakeholders scattered globally. Coordinating this through physical documents and email attachments is technically possible but practically absurd.

Cloud platforms make geography irrelevant. Stakeholders work from identical, current documents regardless of location. Updates propagate instantly. The coordination overhead that typically consumes hours of administrative time largely disappears. In an environment where deals can collapse over delayed information flow, this is not a luxury.

The Business Research Company notes significant growth in insolvency software markets, driven by exactly this complexity. As cases become more international and involve more parties, digital infrastructure shifts from competitive advantage to basic requirement.

The Resistance

Yet adoption remains patchy, particularly outside major firms. The reasons are predictable: upfront costs, integration challenges with existing systems, staff training requirements, and simple inertia. For smaller practices handling straightforward domestic insolvencies, the business case can look marginal. Why invest heavily in technology for problems you have managed adequately for years?

The answer is that “adequately” is a declining standard. Clients increasingly expect the responsiveness that digital systems enable: immediate access to case information, rapid turnaround on queries, seamless coordination across stakeholders. Creditors who experience efficient digital workflows in one case will notice its absence in others. Courts and regulators are themselves digitizing, making electronic engagement standard practice.

More fundamentally, the economics of insolvency work are changing. Fee pressure is constant, case complexity is rising, and efficiency gains are no longer optional. Firms that automate routine document work can deploy their staff on higher-value activities. Those that do not find themselves spending expensive professional time on tasks that software handles better and cheaper.

The Uncomfortable Reality

The insolvency profession’s slow embrace of document management technology reflects a broader conservatism that serves it poorly. The work itself (navigating complex legal frameworks, negotiating among competing stakeholder interests, maximizing recoveries from distressed situations) requires deep expertise that technology cannot replace. But that expertise is wasted when practitioners spend it on administrative drudgery.

Digital document management does not transform insolvency work. It simply removes obstacles that should never have persisted this long. The technology is mature, the benefits are demonstrable, and the competitive pressure is mounting. Firms delaying implementation are not being prudent. They are falling behind, slowly but inevitably, in ways that will become apparent only when clients and creditors start looking elsewhere for more responsive service.

The question was never whether digital document management would become standard in restructuring and insolvency. It was only ever a question of which firms would adopt it early enough to benefit and which would be dragged into modernization by client demands and competitive necessity. That sorting is now well underway.